The Generation Game

Simon Reynolds

01/06/2023

There’s some funny stage banter from a Doors concert that appears on the posthumous Jim Morrison album An American Prayer (1978). “Listen, man!,” the singer shouts blearily. “I don’t know how many of you people believe in astrology”. Shouts of assent rise from the audience, and a woman screams out Morrison’s star sign. “That’s right, baby, I am a Sagittarius,” Morrison answers, adding, with apparent pride: “The most philosophical of all the signs.” Someone in the crowd – possibly the same woman – shrieks “me too!”. There’s a pause and then, with perfect comic timing, Morrison flips the script: “But anyway, I don’t believe in it – I think it’s a bunch of bullshit, myself”.

I remembered this between-song interlude while pondering the concept of generations: the belief that demographic cohorts are united by a shared outlook or mentality. You know the score: baby boomers, Generation X, millennials, Generation Z. It suddenly struck me that generation theory and astrology have a lot in common: they’re based on calendrical units of time and they posit mysterious forces that bring populations into alignment with each other in ways that transect the multiple other ways in which those age groups are divided and differentiated.

Let’s start with my own attitudes to both these forms of knowledge. I’m totally with the Lizard King in reckoning astrology to be “a bunch of bullshit”. But just as Morrison seemed able to combine dismissive skepticism and enjoyment of the idea that Sagittarians like himself had particular characteristics, likewise in my life I have idly glanced at horoscopes in newspapers. I even had a proper reading done once, courtesy of a friend at university who truly believed in the divinatory powers of astrology. Just like with the Tarot, you’ll always find correspondences to one’s life experiences or personality – the discovery that my Gemini-ness was counteracted by a strong influence from Cancer seemed to explain why the traditional hallmarks of the Gemini were muted in my character. My astrology agnosticism was perfectly capable of coexisting with enjoyment of it as a game.

Much the same applies to generation-ology. Recently I learned to my surprise that rather than belonging to Generation X, as I’d long assumed, I am actually one of the last of the baby-boomers. Being born in 1963, at the tail end of the boom, did actually seem to explain something about my outlook: deeply attracted to the ideas and idealism of the Sixties, while having that characteristic X sense of being born too late. (I was also born just a little late to be involved in punk – in many ways a renewed burst of that Sixties belief in the power of rock, the last blast of boomerism). As with Cancer’s dampening effect on Gemini, my baby-boomer mindset was heavily creased by Generation X’s crippling irony, its feelings of futility and exhaustion.

Talking about generations as if they really existed and had sway over people is much more respectable and widespread than the belief that events and personalities are governed by the movements of the planets. But is there really much more substance and reality to “generations”? If not “a bunch of bullshit”, the discourse of generations is certainly generative of bullshit: tenuously grounded overviews and opinion pieces, specious analysis and analogies, platitudes and truisms. And yet, like astrology, it is a fun game to play along with. And far more than astrology, it’s a mode of talk that partially constitutes its object: generalizing about a generation actually brings it into semi-existence, shaping how people perceive themselves and how they are perceived by earlier or later generations. What may just be an illusion, a shaky set of alleged affinities, becomes a social fact.

In this essay, I play along with the idea of the generation, and with related concepts like the decade and the era (whose near-synonyms include the epoch, the age, the period, and the notion of the Zeitgeist). I take them seriously while simultaneously withholding full credence (a very Generation X trait, as it happens: an equivocation, a knack – or curse – of putting everything in quotations marks). Yet I don’t dismiss these ways of looking at history and dividing up populations as completely groundless. Even the most tough-minded sceptic should to be able to accept that moods or outlooks seem to mark out particular phases of time or be commonly felt by many people of a certain age. (The proximity of “age group” and “age” as in era, epoch, etc, seems notable). Are there ways in which these nebulous concepts can be sharpened, so that they become tools with a less tenuous and more tenacious grip on historical realities? Somewhere between rigid-minded credulity in calendrical determinism and a dour rationalism that rejects all talk of “spirit of an age” as mystical guff, might there be a path that acknowledges the power of fancy and speculation as both analytical prisms and as forces that drive and shape history itself?

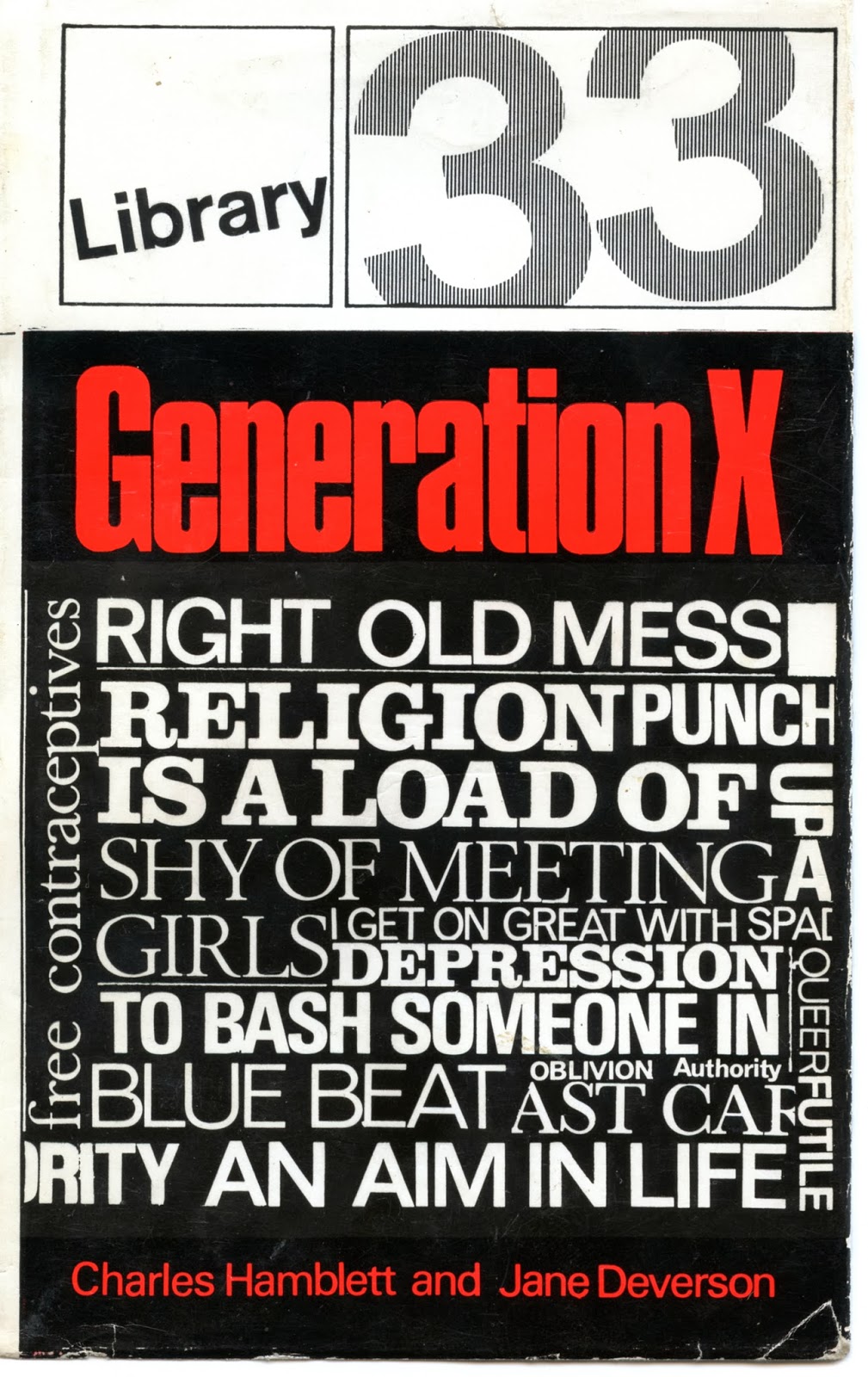

Charles Hamblett & Jane Deverson, Generation X, first edition, 1964

The Structure of Feeling

If you are casting around for a less mystical, seemingly more materially grounded and rigorous concept that does some of the same work as Zeitgeist, there are various candidates within critical theory and academic scholarship over the last half-century or so: among them Michel Foucault’s episteme 1 and Raymond Williams’s “structure of feeling”2 . More recently, there has been affect theory, an arsenal of ways of grasping and articulating the semi-intangible moods and vibes that pass across a population during a particular period: a way of tracking what has been called “the emotional weather” – in other words, feelings that are individually felt but not sourced in an individual’s private life, instead public emotions experienced in common across swathes of the population.

Episteme is a less touchy-feely concept. First used in Foucault’s The Order of Things (1966), it refers to the conditions of knowledge that prevail in a culture and during a particular era. Foucault posits underlying “rules of formation”: “a regime of truth” that governs what is considered to be legitimate knowledge. With his studies of prison, mental asylums, and hospitals, Foucault’s particular concern is the ways that disciplines like penology, psychiatry and sexology generate knowledge that is inextricably bound up with practice (ways in which bodies and populations are treated, punished, cordoned off; how behaviours are “cured”, channeled, elicited and encouraged). But with a little bit of extension, the episteme could be seen as a larger, looser framework of assumptions (a structure of perception, maybe, rather than feeling) that constitutes how a society understands itself and explains itself to itself. Foucault’s thinking, as it develops in the later works on sexuality, also allows for the possibility of dissensus and discrepancy: there is the official episteme, but there are also “forbidden popular knowledges”.

Astrology, in fact, would be a good example of one of these, as would any number of superstitions, mystical or magical beliefs, pseudo-sciences like positive thinking and motivational therapy, and so forth. “Forbidden” doesn’t really work, though: these forms of unofficial knowledge might be disdained and disapproved of by reason-minded professionals and the educated, but in knowledge-pluralistic societies, they are allowed to exist and stake their claim on popular consciousness. As a result, the contemporary political-discursive sphere is riddled with counter-knowledges: conspiracy theories and alternative facts run rife, the credulity of their adherents matched paradoxically by a deep distrust of policy-makers, mainstream news media, and technocratic expertise.

Although much of his work was historical, involving deep excavation of the archives for traces of the discourses of earlier eras, Foucault also characterized his project as a history of the present: an attempt to treat the contemporary horizons of thought and knowledge not as a peak stage in enlightenment’s ascent to clearly perceived truth but just as bounded by hidden strictures and blinders as any earlier historical stage.

“Structure of feeling”, Raymond Williams’s deliberately oxymoronic formulation, moves into a moister, fuzzier zone that encompasses sensibility, attitudes, values and beliefs. These permeate the entire social field and give it coherence (hence “structure”), manifesting in conventions, habits, and idioms in the realms of behaviour, speech, and leisure activity as much as in work, organized religion, and official politics. First aired in a 1954 book about film, “structure of feeling” as it developed became a dynamic and supple alternative to Antonio Gramsci’s notions of hegemony and “common sense”, which emphasized the top-down imposition of ideology through institutions and dominant discourses. Williams’s further concepts of “residual” versus “emergent” usefully allow for the possibility of change and conflict, the gradual coalescence of a new structure of feeling from within the existing and majoritarian matrix. “Residual” refers to traditional ideas and customs that persist in the present, while “emergent” refers to marginal, minority views and attitudes that are the herald, within the now, of how things will be thought and felt by a larger proportion of the population at some point in the future. The warp-and-weft of residual and emergent tendencies constitutes the tapestry that is the current moment. Moreover, any cultural or social phenomenon that achieves not just mass popularity but real significance will tend to contain both elements within its fabric.

More than episteme, structure of feeling seems like a useful concept for approaching the idea of “generation” . When combined with Williams’s notion of residual and emergent, you can see how generation gaps come about: a new formation of sensibility emerging out of the older formation, simultaneously in opposition to it or pulling away from it, while also inheriting and adapting traits of the precursor. The eruption of punk in the mid-1970s is a case study for this kind of phase-shift and transition between generations. What is initially striking – and disruptive – is the way that punk rockers took aim at the preceding 1960s consensus: they outrageously and provocatively inverted the previous value scheme (love and peace replaced by hate and chaos). Yet on a deeper level, there’s a continuity within a larger trans-generational formation in which certain assumptions about the power and purpose of music not only abide but are revivified: the identification of youth culture with rebellion and radicalism. It’s just that with punk, the rebellion is both against the conservative parent culture and against the “older sibling” culture of stagnant and compromised 1960s progressivism. Moreover, in practice, many 1960s people in their late twenties and early thirties got involved in punk, as managers or the founders of record labels – in some cases, even playing in bands – and they would modify their clothing, the length and style of their hair, their speech and slang and even accents to adjust to the new structure of feeling.

The fact that one’s birth date is not necessarily something that chains you to one structure of feeling and prevents you adapting to the new regime of sensibility raises some questions about the concept of the generation, though. How is generational consciousness transmitted and installed? In what sense is it really indexed to age? Not only are there examples of older people who transition relatively easily into the emergent mode of thinking and feeling, there are those who in calendrical terms ought to belong to the new formation but in fact have an “older” outlook (I think here of the 18, 19 and 20-year old hippies I met in my first year at college, at a time – 1981 – when the youth music of the day was New Wave and postpunk). Or they might simply be outside the game of generations altogether, having little interest in music or clothes (the things that typically bear the strongest markers of generational consciousness) and instead being more involved in pursuits or passions that aren’t indexed to age groups in the same way (science, outdoor activities, electoral politics, etc).

Probably most of us can think of people we’ve encountered who don’t seem to belong to the same era. In my second year at university, my friends and I “adopted” a young man with old-gentleman’s mannerisms and views. We enjoyed William’s anomalous clothing and opinions (which would have placed him in the 1930s, or at a push, the early pre-rock’n’roll 1950s). No doubt it was equally the case to say that William adopted us, enjoying the frictional element to our socializing and relishing his own rebarbative reactions to the trendy ideas about feminism and post-structuralism we spouted. To some extent, he reflected an archetype of the 1980s, the young fogie: a counter-hegemonic reversion to how things were before youth culture and the rock era (when young men aspired to look and behave middle-aged, smoking pipes and wearing a suit and tie) that in some sense paralleled the push of Thatcherism to roll back all the gains of the 1960s. But William’s out-of-time quality seemed more ingrained in his psyche: he just didn’t belong today.

Equally, one comes come across people who refuse to stay where they belong generationally: the aging Sixties hippie who plunged into the 90’s rave scene, for instance (at once rare enough to be remarkable but at the same almost an archetypal figure on the scene). Some people seem to have an inborn facility for sliding from youth scene to youth scene even as their age in years accumulates. Like human anachronisms and characterological throwbacks such as William, these younger-inside-than-they-look-outside types weaken the notion of the generation as a kind of quasi-biological birthright that is the common property of people born within a certain span of dates.

Yet those of us who are no longer young encounter this sensation all the time: the friction and frisson of a palpable generational difference. Especially if your job requires you to be in the presence of people half your age or less (such as a teacher of college students), but also when in the company of your kids and their friends, you notice this gulf, manifested most pungently through humour and language. Some of it comes from having a different set of cultural memories and formative experiences with art and entertainment. But it's also a vibe (and here “structure of feeling” and affect theory come into view again) that goes beyond taste and that has an almost biological tang to it: like the smell given off by a different species.

What forces generate and condition generational differences? One underlying causative factor could be changing patterns of parenting. My generation was shaped by the adoption of progressive child-rearing ideas (picking up an infant when it cried, rather than leaving it to “cry out”, an abundance of cuddling and tactile affection, the phasing out of corporal punishment). Subsequent generations have been affected by even more permissive styles of parenting and teaching: treating children as mini-adults when it comes to consumer choice, the fashion for avoiding prohibitive language and using negotiation or bargaining to elicit desired behavioral outcomes, “helicopter-style” parenting that doesn’t allow children the kind of free-roaming autonomy that was the norm for pre-pubescent kids when I was one, parents who allow small children to sleep in the marital bed for much longer than was thought proper in the past. These trends no doubt mold the growing psyche and affect the young person’s stance towards the world. These changing approaches to care and education would indeed contribute to the formation of a new “structure of feeling”.

Other factors might be historical: what actually happens, politically and economically, during the formative years of a generation. Growing up during World War 2 and the rationing that continued for a decade even after victory molded the expectations and attitudes (and doubtless had physiological effects too) of the generation of British youth that preceded my own; another factor would be the ending of compulsory military service for young men at the start of the 1960s. Likewise, the demographic cohorts that at a tender age lived through destabilizations like 9/11 or covid and lockdown are also likely to bear a particular imprint. Yet another set of factors involve technology: a generation that grew up with smartphones and social media is going to be wired differently than an earlier generation who has embraced those tools but retains embedded memories of how things worked in a different age. Then there are the different impacts caused by pop historical sequence and cultural chronology: people who witnessed in real time the emergence of rock’n’roll seemingly out of nowhere have a different feeling about the music than those who grew up 20 or 40 years later when rock feels like it’s always been there.

Generations are also constituted by the feedback loop of market research and newspaper reports. Opinion polls and surveys, statisticians and trend watchers extract data from the population or specific strata thereof; this fuels media articles about shifts in attitudes, aspirations, and anxieties. Like a mirror with the power not just to reflect but to sharpen the image, mediatized analysis of purported generational attributes becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, shaping how a particular age group or demographic understands itself.

Cool-watchers and market researchers work directly for companies that want to get a grip on the fluctuating desires of consumers. Then there are psychologists and sociologists who write mass market non-fiction: researched but non-scholarly books that are accessible to the layperson and in some cases become best-sellers or get a lot of attention in the media (an example would be Dr Jean Twenge, a psychology professor who’s authored book-length diagnoses of millennial mentality such as Generation Me (2006), The Narcissism Epidemic (2009), and iGen (2017)). In an indirect sense, these academics could also be said to be working on behalf of big business and government, since their overviews and character typologies influence advertising campaigns and policies. But at the journalistic level, opinion pieces about generations tend to concoct their conclusions out of a mish-mash of statistics, anecdotal observations, semiotic readings of cultural products (songs, stars, films, TV series, games, trends, memes), and speculation. The art form of these kind of pieces, and the business of it (clicks) rewards the sweeping and attention-grabbing conclusion, rather than the nuanced and tentative claim.

(I’m thinking here of my own past writings about Generation X – not a term I used much at all, but I did talk quite a bit in the early ‘90s about the Slacker. Starting in the late ‘80s, alternative rock and indie music revolved around a set of overlapping attitudes and affects that included resignation, withdrawal, cloudy-headed drift and disengagement from politics. This born-to-lose (dis)spirit broke into the mainstream with Nirvana and the grunge movement, while also finding crystallization in Richard Linklater’s cult movie Slacker (1991). The latter was set in the Austin, Texas milieu of post-college lay-abouts forming half-assed bands with names like The Ultimate Losers. (Linklater’s next film Dazed and Confused (1993) found a pre-echo for this ‘90s mood of blissed-out burn-out in the pre-punk 1970s). The slacker archetype was sociologically real and there was plenty of subcultural and sonic evidence to support the idea that this was a Zeitgeisty archetype. Yet as I energetically wrote about the movie and bands of the “slacker rock” type, divining all kinds of significance in their bleary vocals and blurry guitars and the “Zen apathy” themes in songs like “Everything Flows”, it somehow slipped my attention that I for one was anything but a slacker: in fact I was a virtual workaholic, prolific, driven, and ambitious. As in fact were many of the bands who most potently embodied generational impotence in their music and image: they toured heavily, recorded often, and in most cases, signed to major labels when the opportunity presented itself. They made a career out of an aesthetic of anti-careerism.)

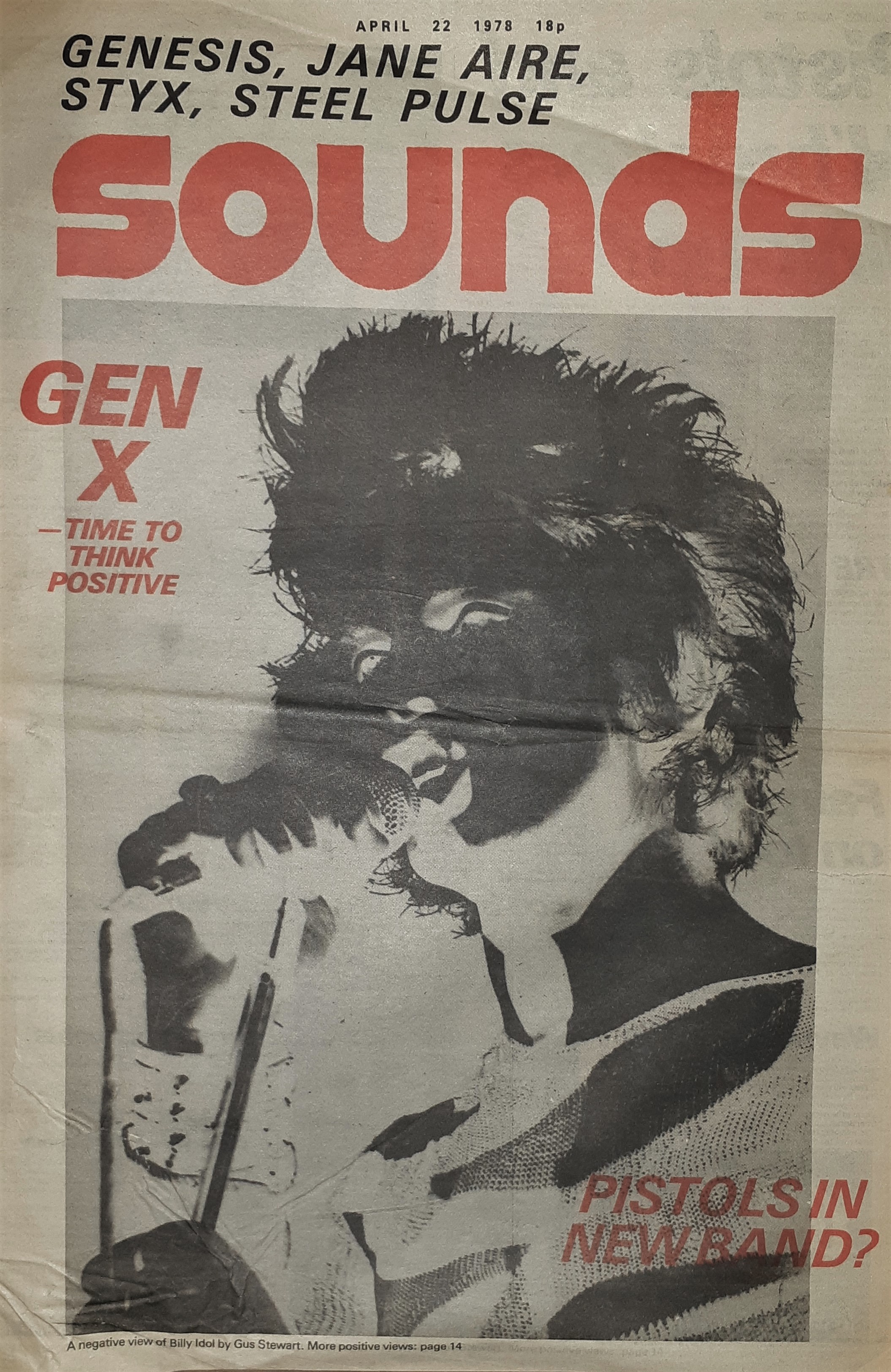

Sounds, magazine cover, april 1978

The Art of Decades

Still, with the generation game, for all the ironies, over-sweeping claims and contradictory evidence swept under the rug, there usually is something there. Decades-based analysis is by comparison the sheerest form of calendrical mysticism. Although the fervour for this kind of thing has faded a bit, people remain attached to the idea that the decade (an arbitrary division of historical time) should have some kind of essence or unifying “feel”. But since any sensible survey of past centuries indicates that eras don’t start punctually at the switchover point between numerical decades, people started to work around it with concepts like the Long Sixties: the idea that the 1960s didn’t really wind up until 1973, when the oil crisis and the resulting economic contraction brought about a shriveling of the sense of possibility that had reigned through the preceding decade. But if a decade actually lasts longer than ten years, and reaches its cessation point several years after its numerical end, that makes a nonsense of the demarcation of history into decade-length portions!

(Less tied to the decade switch-over point, but still fanciful was the cyclical theory of pop history: for instance, the proposition that revolutions always happen in a year that ends in ‘7 (1967 as psychedelia, 1977 as punk… it fell apart just a bit when 1987 rolled by, among the most uneventful of pop years ever!).

As with generations, decade-consciousness becomes a self-fulfilling fallacy: if enough people think they’ve entered a new era designated by the arrival of a year that ends with a zero, this becomes a social fact, or at least, a discourse. People – younger people in the main – crave to be part of a moment that belongs to them; media awaits the arrival of a new-decade-feeling eagerly; there are always candidates jostling to be heralds of the Next Vibe. Glam rock is partly attributable to a desire on the part of teenagers for music that was different from their older siblings’s sound; Bowie saw himself as a weathervane artist, someone who would be for the ‘70s what Dylan or the Rolling Stones had been for the ‘60s. Inchoate youth longing combined with career advancement on the part of individual artists like Bowie and Bolan to get the new Geist aloft. A buzz term at the time, started by Alice Cooper and widely adopted, was “third generation rock” – the first generation was those who’d witnessed ‘50s rock’n’roll happen in real time; the second had seen the Beatles and Stones wave of bands evolve from tough rhythm-and-blues to psychedelia and hippie rock; but now, in 1971, a third wave of youth desire was casting around for representations and representatives that belonged to them alone.

The glitch in this theory, of course, is that many of “the third generation” in terms of their age were actually not taken with glam and were actually happy to carry on in alignment with late ‘60s values, listening to those bands or bands who were sonically a continuation of acid rock and heavy music, dressing and drugging accordingly, and continuing to wear their hair long and faces bearded. Equally, some of the Third Generation bands, like Mott the Hoople, who recorded an anthem for the Coming Demographic Wave in “All the Young Dudes” (the lyrics make fun of Sixties groups who believe in all that revolution jive), were actually, in age terms, members of the second or even first generation (singer Ian Hunter was old enough to remember rock’n’roll arriving in the UK). Black Sabbath, who carried on and extended the “heavy” aesthetic started by Cream, were actually younger than Mott the Hoople. Sabbath and Led Zeppelin defined the new decade of rock easily as much as Bowie or Mott or Roxy did, if not more.

Decades – when they start, who represents them – are debatable. Like with generation-talk, that’s their point: to be bones of contention, sites of argumentation. What William Gibson said of the future – it’s already here but it’s unevenly distributed – could be applied to any of the cluster of generalizations that are amassed in the positing of a generation-spirit or a decade-feeling. In other parts of the world or different regions of a country, within a population or across an age-group, there are varying degrees of participation and attunement to Zeitgeist. Do notions about generations, or decades, apply with equal force in Norway as they do in the U.K.? In Mississippi, as they do in California? It’s long been a joke that if you can remember the Sixties, you weren’t there. But many people remember the decade perfectly well because they were living in a totally different Sixties, a non-swinging and undrugged decade. Likewise, characterizations of Generation X as defeatist are belied by the large number of young people engaged in activism during the ‘90s.

Just as with the generation game, talking about decades is good fun. I once participated in a cluster of collective blogs, each of which was dedicated to a different decade: the 70s, the 80s, the ‘90s. The blogging was among the most interesting and entertaining I’ve read. It worked best, though, when the contributors focused on discrete cultural products of an era: a rock group or record, a certain film or TV series, a politician or an advertising campaign. In fact, I don’t recall anyone ever making any sweeping statements about supposed decade-defining principles. The blog worked for its writers and readers as an immersive plunge into the specificity of the past, like a more analytical version of those enjoyable I Love the 70s / 80s / 90s television shows with their gallery of fads, celebs, hits, and scandals. These fragments, like the shards of a shattered hologram, seem to capture the quintessence of the whole era, but only as a glinting hint, an aroma almost.

Decades – like generations, and like eras and periods – are fables: fictions with a grain of truth. The game of taking them for real has real effects. If you believe you are swinging, or swinging again (as with the Britpop mid-90s replay of the ‘60s), and the media propagates and amplifies that feeling until enough people believe it’s happening and hurry to join in – soon enough, sure enough, you’ve turned the story into something closer to a shared reality. Hyperstition is a term coined by accelerationist thinkers in the ‘90s to describe this process. But really if you drop the “rstition” and leave it at “hype”, you are talking about one of the oldest maneuvers in the world: the confidence trick, the “true illusion” pulled off by shamans, mountebanks, impresarios, hucksters and stage managers all across history.

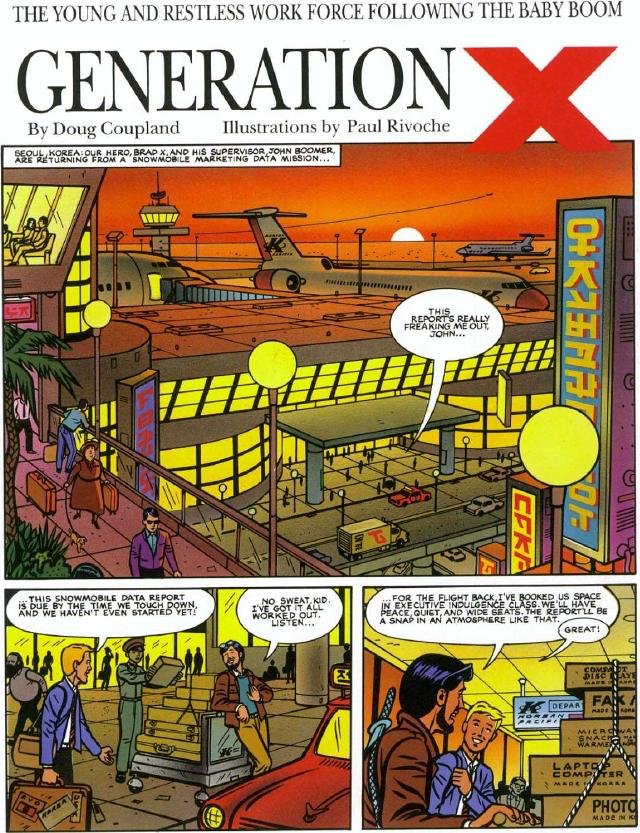

Douglas Coupland, Paul Rivoche, Generation X, comic strip published in Vista Magazine (Toronto, 1988 - 1989)

Simon Reynolds is the author of eight books, including Rip It Up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978-84, Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past, Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture, and Shock and Awe: Glam Rock and its Legacy. He is a freelance contributor to Pitchfork, New York Times, London Review of Books, and The Wire. He also operates a number of blogs centered around the hub Blissblog. Born in London, Reynolds spent much of the 1990s and 2000s in New York and currently lives in Los Angeles, where he teaches classes on DIY, art-pop and “the Elastic Voice” in the Experimental Pop program at the California Institute of the Arts.