The Rave Continuum: Plot and Politics of Europe’s Last Youth Culture

Persis Bekkering

03/01/2023

"No narrative, no destination."

Simon Reynolds, “The Hardcore Continuum”, The Wire, 1992

PART I: COLLECTIVITY

1.

As a beloved theorist once asked: Why should the rave ever end?1 Continuity and repetition are the rave’s crucial components. With its sustained high intensity and long (preferably endless) duration, the rave has a specific relation to temporality. It poses a challenge to the normative chronopolitics of the working day, or the bourgeois plot. A raver is the rascal of the picaresque, stumbling through nocturnal episodes without ever learning anything about life.

Yet in popularized depictions and narratives about club culture, there always comes a day in which the raver abdicates.2 “Don’t forget to go home”, as the title of a famous Y2K documentary on Berlin’s club scene admonishes us.

The classic plot follows a familiar narrative arc, the unbreakable backbone of western storytelling. First comes excitement, the discovery of another world; absorbing, full of promises and dreams of excessive pleasure and new friends. Rave is discovered as a complex aesthetic universe, providing ample apprenticeship to those with nerdy proclivities, but it is immediately accessible to newbies and amateurs as well.

Sooner or later, the raver unavoidably gets too absorbed. He loses itself in lack of sleep, drug addiction and empty consumption of bodies. Years of dancing and collecting records, moreover, have made him into too much of a connoisseur, a snob; it’s almost impossible to be met in his tastes. Wherever he goes, it all sounds the same to him, lame and commercial.

Finally, he (always a he) wakes up from the dream. This part is called The Comedown. The poor guy, broke and weakened, traverses the fantasy and returns to supposedly normal circadian rhythms. He has lost a few illusions and some years of his life, but gained insights in the vicissitudes of being a subject in today’s world. Most of all, he has learned to control himself. His drives are sublimated by the reality principle at last.

As spectators, we feel relieved. The light has conquered over the dark. The superstructure vindicates, bourgeois values are restored. The transgressive, subversive forces have proven to be a sham. At least, we tell ourselves, he had fun.

One day it just has to end, a friend in club retirement recently explained me. You can’t go on forever.

It sounded like a universal truth. Rave belongs to the youth.

Maybe I’m still on the A-side of my fantasies, but I resist yielding rave to the imperatives of the organized plotline we call “adulthood”. Because indeed, why should the rave ever end?

It hasn’t ended, anyways. Even two years of enforced closure couldn’t kill it; the only thing that changed was its legal status. The rave plot is flat, plane-like, like a postmodern novel, or again, the picaresque. Resilient to progress, to coming-of-age, even to the eschatological lures of utopia. Rave is a continuum, a trance inducing drum that started banging somewhere in the eighties and continues, somewhat a- or polyrhythmically, until today.

But then again, what is the narrative structure of the rave? Maybe the story reads like one of those unstable moments of trying to make your way through a packed dancefloor after hours of snorting ketamine off a rusty key, pleasantly bouncing against shoulders, stepping on toes, groping in the dark, only to find out you are walking in circles.

Excruciating. But fun.

Zuzanna Czebatul, MACROMOLECULE EXPLOITING SOME BIOLOGICAL TARGET, 2021. Photo: Bert Heinzelmeier.

2.

Nothing left to dream. Climax, anti-climax. Repetition, endless repetition. A thousand plateaus of crescendo. You’ve been turned inside out and all that was inside you swings from your arms, floating like paper streamers in the air, and now the wind has died down. Go sit somewhere. You don’t feel it but you can hardly stand. A quick calculation should convince your brain that you’re tired. Go, take a seat. You feel great, you eat an apple. The juice trickles down your chin, it’s never tasted so intense. You show it to whoever is sitting next to you. Whoever is sitting next to you licks it off. You’re surprised by the sudden appearance of a face in front of yours, a tongue protruding, growing in size, a formless sea creature. Then your own emerges, as if suddenly borne out on a strong, warm current. Your body tingles as your sliding tongues touch. The tongue is cold from the chilled Coke that just ran down it. But you don’t taste the Coke, you taste the body.

A drop falls onto your shoulder. You look up, but there’s nothing there. The ceiling? Collective sweat off the ceiling. You may as well rub it into your glowing skin, because if you don’t sweat, use that of others. The girl sitting next to you recoils audibly from this act, which is both clever and disgusting. She presents you with a light, but it’s difficult for you to put your cigarette to the flame. Your shoulders move mechanically, as they have been for hours, held by the music.

You get up again, light as an empty cardboard box. You love this track, don’t want to miss a thing. It’s impossible, this. What is this? Who knows this track? Soon it’s over, with new beats undermining the previous ones. You wanted to be part of it, to be lifted up, but every time you’re too late. You wipe your hair from your face, keep dancing, repeating movements, always at the ready. One day, you’ll look the moment in the face, grab it by the cheeks. You stand with your eyes closed, seeing golden lights swirling in a deep purple tunnel. When you open them, the tunnel is gone and you’re among all those hot people again, all those steaming bodies. You feel their presence behind you, next to you, surrounding you without touching you. You reach up into the air, you rhythm machine, and the longer you keep doing this, the better it feels, air flowing underneath your wings. Sticky air. Still air. Repeat.3

3.

For the last couple of years I’ve been researching rave culture, as it emerged in the second half of the eighties in Europe, and as it continues to exist, at least as a murky notion, if not a half-destroyed culture, until this day. I am working with the murkiness of that notion here. ‘Rave’ not merely designates the specific subculture of the eighties and nineties, of working-class youths gathering in open fields or abandoned factories blasting hardcore techno – the subculture often described as Europe’s last big youth movement4 . In my understanding, rave functions as umbrella term for the phenomenon in the widest sense, designating a mass – any mass - of ecstatic people dancing to electronic beats (any bpm between downtempo and hyperspeedy terrorcore); and the masses are still dancing. I call it the Rave Continuum. The scene might be a little less massive than back in the days. We are mostly destroyed after two years of pandemic sanitary regulations. But we haven’t gone home yet.

Although the initial impetus was rather instrumental, oriented towards the laborious and disciplined process of writing of a novel exploring the affective dimensions of living in a world in crisis, the research has somehow taken a life of its own. (Became its own continuum.) Some short stories, essays, a performance, workshops, reading groups and talks have ensued.

Mine is not a historiographical or ethnographical approach; I’m not an archeologist of rave culture and the many musical genres for which the term is a hosting body. I am interested in the temporal dimension of the rave. Something happens to time when immersed in a multitude of sticky people on a dancefloor. It speeds up, it slows down, and afterwards, it proves impossible to recount.

Eventually, I came to understand rave as vanishing point – a vanishing point for the individual subject and subjectivity, for language, for the linear unfolding of history, for the chronological arc of the classic story. Everything gets sucked up and reshuffled, leaving no traces, until you walk out into the day again, squinting against the light, a little confused about what just happened. Discourse had fled those dark corridors a while ago.

4.

From Rainald Goetz’s 1998 novel Rave5 :

Once upon a time, there were not yet words for all this here. It just happened, and you were in the midst of it, you watched and had some kind of thoughts, but no words.

Does that even exist? Maybe only inside, in the mind?

Sure, always.

It was the wordless time, when we were always looking around with our big eyes so strangely in every possible situation, shaking our heads, and could almost never say anything but:

Speechless –

Pf –

Brutal –

Madness –

Speechless, really –

[…]

Reckless as it might have been, at the same time this experience was yearning to understand itself. And yet wanting at the same moment to forget itself again, to destroy understanding, to have some new experience reveal that understanding to be nonsense invalidated through novelty, tumult, coolness.

5.

If rave is a vanishing point, a vortex in history, how to represent it in narration? And is the crisis rave presents to narrative writing also pointing to a bigger crisis – or accumulation of crises – of today?

Rave proposes a different logic than that of the working day. Let’s call it the logic of the night. A fractured, polyrhythmic logic. Therefore, I propose this text as a guide of sorts, through the materials I’ve gathered. As if I were the guide through my own archive, but one that is too excited by the topic herself to make a lot of sense, or maybe as one too high on speed to build a solid structure. I imagine it as conjuring up an echoic choir of voices and images of others, most of them ravers and clubkids of the past and today, surrounding myself by “all those steaming bodies”, “their presence behind me, next to me, surrounding me without touching me”. A thousand plateaux of crescendo 6 , to borrow the words of Simon Reynolds.

6.

From Guillaume Dustan’s In My Room:

Night people are the most civilized of all. The most difficult. They pay more attention to their behavior than aristocrats in a salon. At night, you don’t talk about obvious things. You don’t talk about work, or money, or books, or records, or films. You only act. Speech is action. Always on the lookout. Gestures charged with meaning.7

7

“The sixties-style ‘tribal gathering,’ the forest conclave of eco-saboteurs, the idyllic Beltane of the neo-pagans, anarchist conferences, gay faery circles... Harlem rent parties of the twenties, nightclubs, banquets, old-time libertarian picnics — we should realize that all these are already ‘liberated zones’ of a sort, or at least potential Temporary Autonomous Zones. Whether open only to a few friends, like a dinner party, or to thousands of celebrants, like a Be-In, the party is always ‘open’ because it is not ‘ordered’; it may be planned, but unless it ‘happens’ it’s a failure. The element of spontaneity is crucial.”8

It’s unavoidable and perhaps a little naïve to read the rave alongside the ideas of (problematic) anarchist Hakim Bey (aka Peter Lamborn Wilson), whose mystical writings were infused with eighties No Future pessimism, while still avowing a strong attachment to hippie dreams. Besides being accused of paedophilia, he is mostly famous for coining the notion of the T.A.Z., the temporary autonomous zone. A T.A.Z. is a temporary, spontaneous space or a large gathering that eludes formal structures of control. Allegedly, Hakim Bey liked that ravers took his ideas to heart, if only they would leave out all that techno stuff.

“The essence of the party: face-to-face, a group of humans synergize their efforts to realize mutual desires, whether for good food and cheer, dance, conversation, the arts of life; perhaps even for erotic pleasure, or to create a communal artwork, or to attain the very transport of bliss — in short, a ‘union of egoists’ in its simplest form.”9

@berlinclubmemes

The phrase “a union of egoists” interests me, and how it relates to collectivity. As I dance with my eyes closed in a mass, a rave is not a committed collective, let alone a group collected around altruist, activist ideals. A rave is a temporary gathering of individuals on a dance floor, that within those confines and as long as the rush lasts, will feel like a loving family, like best friends. They hug. They smile. They care. They yell in your ear how much they love you already. They don’t mind sitting with a friend who feels sick, striking their hair for hours in a safe corner.

But there is also hostility. There is violence. There is sexual violation. And when the party ends or the drugs are finished, the solidarity ends, too. Maybe they’ll invite you to someone’s house for an afterparty, where you’ll make new friends. Maybe you build a scene of other queer people in town, and this makes you feel less lonely and precarious. I should also mention the rave protests, that have returned in the streets in recent years, whose prime example is the one initiated by ravers from Bassiani, a club in Tbilisi, Georgia.

But one should not align ravers too readily to activism. More often than not, it’s difficult to mobilize the pack when something needs to be done. Ravers are grumpy on weekdays. Leaving aside physical toll, not much is required of a raver. It used to be cheap, today you’ll need a lot of cash. You can spend all your weekends in the club, but when you stop showing up, no one will ask why. I wonder if maybe, in that temporary gathering that is so reluctantly mobilized for action, for a future goal, for policy making, or for production, if maybe in that uselessness and ethical ambivalence another space opens up. A space that by its very existence is resistance.

@berlinclubmemes

Bey: “What is the refusal of Art? The ‘negative gesture’ is not to be found in the silly nihilism of an ‘Art Strike’ or the defacing of some famous painting — it is to be seen in the almost universal glassy-eyed boredom that creeps over most people at the very mention of the word. But what would the ‘positive gesture’ consist of? Is it possible to imagine an aesthetics that does not engage, that removes itself from History and even from the Market? or at least tends to do so? which wants to replace representation with presence? How does presence make itself felt even in (or through) representation?”10

8.

Clip from Echoic Choir by Stine Janvin and Ula Sickle (2021), a concert performance that premiered at the Wiener Festwochen in Vienna. Echoic Choir attempts to evoke the ritual of rave within the parameters of social distance, only using voice and movement. A synthetic kickdrum is added toward the end for dramaturgical reasons, but the rest consists of rave’s raw materials. Can one summon the feeling of immersion and collectivity, borrowing rave’s aesthetics and ideology without the physical proximity of melting bodies?

Six performers are dispersed throughout the space of the venue, making the audience an integrated part of the ritual. They build up sequences of polyrhythmic beats deploying more ancient musical structures, such as the hocket and the fugue. A very minimal, stripped-down version of a dance floor, a blueprint.

9.

I wrote an essay accompanying Echoic Choir. “A world without dance floors is like a world without nights. That’s not just to say the dance floor is the metaphorical space for transgression, for the unmediated flow of drives, as the night is the time for ghosts and fears and dreams to come out. It’s true that a rave provides, in a way, the conditions for boundlessness, for excess, for the expression of that which is otherwise crushed by society’s normative tendencies. But that might already be too specific. In its most abstract sense, it’s saying this: there is a necessity to the dance floor. As with the function of sleep, the dance floor resets bodies. Dancing synchronizes bodies to a collective rhythm, and therefore, to the idea of the collective itself. This seemed obvious for a long time, until it didn’t.”11

Dancing together as a praxis that synchronizes bodies in a collective rhythm against atomization, is an idea I borrowed from curator and artist Bogomir Doringer, who is researching dance floors, especially moments when they spill out into political action on the streets. I like to think of a rave as synchronization.

10.

But I used to put it more strongly: at the party’s best moments, the I dissolves and reemerges as we. Dancing as collectivization. Somehow, I stopped believing this. The I dissolves, yes. The impossibility to assemble discourse is testimony to this. But not in favor of the constitution of a collective. The vortex only spits out fragments and parts. It is a force of entropy, of destitution.

This is not a more pessimistic frame.

11.

PART II: CRISIS

12.

Why did rave emerge? Why does it even exist?

My insistence on repetition as a constitutive element of the rave recalls Freud’s words of the workings of trauma, and its “compulsion to repeat”. Trauma can be recognized the second time only. Trauma tends to return to the ego disguised in the form of patterns, habits, addiction. Trauma wants to be rehearsed, repeated, sustained. This repetition is not necessarily a Sisyphean punishment. It also provides the occasion for Durcharbeitung, for the insistent working-through the same material until a new path is carved out, until the elements are rearranged in another order.

I started thinking about rave as a phenomenon that bears a relation to a compulsive repetition, as a symptom of trauma. The never-ending rave, the club without closing hours might be the space that charitably hosts such repetitive compulsions. Or perhaps it could provide occasion for sublimation; pacifying trauma by giving consent to and staging the brutality of history inside the narrow concrete walls of a reappropriated space. (Excruciating, but fun.)

13.

This is another way of understanding repetition: as ritual. A ritual derives its symbolic and embodied meaning from the possibility of being repeated. A gesture that by rehearsing itself accrues and transcends its own history. Transcends individual intention.

Above, an excerpt from a film by British artist Jeremy Deller, Everybody In The Place. An Incomplete History of Britain 1984-1992. In front of a classroom of teenagers, Deller suggests that rave was a death ritual, ‘to mark the transition from an industrial to a service economy in Britain.’ Literally dancing on ruins, in the spirit of Walter Benjamin. In abandoned factories, the spaces where their ancestors worked, working class youths reappropriated histories of violent exploitation, and sublimated trauma into a pleasurable activity. Day was replaced by night. Movement stayed the same; what was once the pounding of the machine was transformed into machine-like dancing, repeating the same clunky, choppy movements over and over again.

14.

From The Hardcore Continuum by British writer Simon Reynolds, 1992:

At raves and clubs, or on pirate stations, DJs compact rough and ready chunks of tracks into a relentless but far from seamless inter-textual tapestry of scissions and grafts. It’s a gabbling fucking mess, barely music, but as it swarms out the airwaves to a largely proletarian audience, you know you’re living in the future. ‘Trash’, but I luvvit. […] It’s a mistake to appraise Ardkore in terms of individual tracks, because this music only really takes effect as total flow. Its meta-music pulse is closer to electricity than anything else. Ardkore has abandoned the remnants of the verse-chorus structure retained by commercial rave music. At the Castlemorton Common mega-rave in May, MCs chanted ‘we’ve lost the plot’. Ardcore abolishes narrative: instead of tension/climax/release, it offers a thousand plateaux of crescendo, an endless successions of NOWs. It’s an apocalyptic now, for sure. […] No narrative, no destination: Ardkore is an intransitive acceleration, an intensity without object.12

15.

Rave exploded toward the end of the 1980s and reached a first apex in the summer of 1988, which got quickly dubbed as the second summer of love, expressing a vaguely felt analogy with the revolutionary spirit of 1969 – a spirit of hope, peace and dissent, and most of all, free love.

Zuzanna Czebatul, MACROMOLECULE EXPLOITING SOME BIOLOGICAL TARGET, 2021. Photo: Bert Heinzelmeier.

I like this recent work by artist Zuzanna Czebatul. It expresses the ambivalence of the rave continuum with emblematic clarity. The object resembles a giant xtc-pill, with on the one side the barely legible word “REVOLUTION”, and on the other (see above), “RUSH”. The two sides refer to the two modalities of rave culture: to its utopian claim of uniting people of all backgrounds, and on the other side the euphoria and freedom of sexual expression fueled by new synthetic drugs as xtc or mdma. The rush thereby entangles the subject with what Paul Preciado coined as the “pharmacopornographic era”13 , updating Foucault’s notion of biopower with the internalized control and technical enhancement of bodies through the intake of drugs. There wouldn’t have been a second summer of love without XTC.

As old clubbers had told me, rave culture was deeply infused with a feeling of historically justified optimism, a sentiment that lingered far into the 1990s. After the struggles of the first half of the decade, culminating in the UK in the miners’ strikes, things started to look more promising. The fall of the Wall and the end of the Soviet Union, the economic boom, the establishment of the European Union, the release of Nelson Mandela from prison. The promise of the internet. For some, the new millennium and its viral threat promised a reset, the possibility of creative destruction.

Francis Fukuyama famously congealed the affects of the era by declaring the end of history. After the decay of communism and other totalizing ideologies, the project of history was allegedly carried to the end. We were living in a world freed of oppressing utopianism and grand narratives. We were finally governed by no one except an invisible hand, living a new world of pure rationality of the market. There was no more alternative. We were living in the best possible world of total immanence.

One way in which this freedom resonated with rave’s grandiose promises was the immediacy of new music production. With the advent of drum computer technology and the development of house and techno music – in respectively Chicaco and Detroit –, everyone could become a producer. Class hierarchies were overturned. No professional formal education was required to enter this sorites of new musical paradigms. Everyone could become famous and rich from within their poster covered bedrooms.

The God of this paradigm required sacrifices. Melody was thrown in front of the bus; rhythm and bass were all that mattered. Melody seemed as obsolete as narrative was. Lyrical mastery, too. A few words would suffice. At best a few words from disco’s classics were recovered: “work it”, “all I wanna”.

Simultaneously, the band was pushed off stage in favor of the disk jockey: crouching behind a stack of records in the dark, the dj was merely a mediator, a selector, a mixer and matcher for beats stripped of subjectivity. As Hacienda-owner Tony Wilson (played by Steve Coogan) says in 24 Hour Party People (2002), a film about the emergence of club culture in Manchester: “Tonight something epoch-making is taking place. See? They're applauding the DJ. Not the music, not the musician, not the creator, but the medium. This is it. The birth of rave culture. The beatification of the beat. The dance age. This is the moment when even the white man starts dancing.”

16.

Where rave sheds subjectivity – through desubjectivized music, but also through the cutting off of sight, in darkrooms and using stroboscopes – , identity appears as its focal point. This displacement of subjectivity to identity was a child of its time. Postmodern sensibility explicitly hailed the free expression of identity, such as gender and sexuality. This zeitgeist permeated the rave movement in bifurcating ways.

Cleo Campert (title and date unknown), courtesy of The RoXY Archives.

In the more artistic clubs of Amsterdam such as RoXY (see image above) and IT, a highly personal identity was encouraged through individualized, unique outfits, original dance styles and extreme behavioral tolerance, often bordering on outright indifference, as old ravers have told me. (As Dutch writer and former gogo dancer Jannah Loontjens recalls in her memoir Roaring Nineties14 , one could work an entire shift crying and nobody would ask what’s wrong.) In the hardcore and gabber scenes of the nineties in the lowlands however, a rather working-class scene (but not exclusively), gender fluidity and equality were not explicitly avowed, yet nonetheless expressed in the universal uniform of the track suit, and a desexualized dance style that didn’t move from the hips, but looked more like one were chopping wood – “hakken”, in Dutch, or in proper vernacular, “hakkûh”.

Gabbers. From the photographic series Exactitudes by Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek (1994).

3Doc Gabbers, documentary ( 2013)

17.

The early rave scene in East Berlin before the fall of the Wall is well described in Felix Denk and Sven von Thülen’s Klang der Familie, a collection of oral histories:

At the beginning, you were like a kid in a candy store. All these little mills and sheds, all empty. In the West, by contrast, everything was closed. There, it was unthinkable to open a bar or club just like that, without much money. […]

Turn the door handle, and you were suddenly standing in a 1,000 square meter space. And every place you opened, you could throw a party. […]

We looked around some more and eventually found ourselves in the control center. All the equipment was covered in a thick layer of dust, but you still had the feeling that the men who’d once worked there had only just left. As though they’d had to leave in a rush. Chernobyl wasn’t so long ago, after all. A very special light shone into the room through the windows. Beautiful.

When I walked in, I thought I’d entered the spaceship Orion. We’ll lift off soon and start a new country.15

18.

The rampant sentiment of optimism that defined the early days of rave paints a distorted picture, however. What were we celebrating, after all? The end of history brought a thousand plateaux of crisis in its wake. To reactivate a dabbling economy, the large-scale implementation of neoliberal policy, whose poster boys were Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, fundamentally reorganized the state, the relation between state and citizens, and the relationships of production. It meant the dismantling of the welfare state, although the velocity of that destruction differed from country to country. Generally, social bonds were sacrificed to enforce economic growth, supported by an ideology of intensified individualism. Instead of jobs, we got projects. The borders between the private sphere of the bedroom and the workplace started to vanish. Labor got increasingly casualized, almost everyone proletarianized; this process of the destruction of social and economic security is far from completed today.

Which is not to say the rave was a paean to this destruction. If the shiny-haired yuppie was the emblematic figure of the financial boom, the bald gabber was perhaps its ante-figure. The lifestyle of parties doesn’t sit well with an 80-hour working week. Against competitive office mentality and the Hobbesean war of everyone against everyone, the gabber proposes collective euphoria, love and creativity. Against the imperative of productivity, the raver offers the possibility of self-destruction and meaningless enjoyment of time stretched. Against the ongoing exposure of domestic life as a site of labor, the club offers a different, much more interesting hybrid of the private and the public: more public, yet also more private.

But it’s difficult to unearth a distinct ideology from the rave continuum. Although today the more underground club scenes such as those in Berlin and Eastern Europe have proved to be allies of anticapitalist, anti-racist and feminist activist movements, at least avowed by mouth, during its first decades, rave never had a political agenda. It didn’t fully or uncritically embrace the optimism of the era. But it didn’t offer a powerful critique, either. If anything, rave was a symptom of history, a somatic response to a fundamental rift. It can only be understood dialectically, as an ambivalent phenomenon that accelerated, celebrated and resisted its time. I agree with Haq, where he describes the movement not as a counterculture that ultimately rebelled against its time, but as an alternative culture none the less16 . It is a vanishing point, or a screen on which we can project anything we want – acceleration of postmodern presentism, resistance against the breaking of the social bond, or even nationalism and far right sympathies.

19.

In the Netherlands, rave parties were rapidly embraced and understood as an extremely profitable new market (firstly by ID&T). In the UK, rave became rather politicized, even legally antagonized. The Criminal Justice Act of 1994 gave the police the power to shut down events “characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”, criminalizing unlicensed raves, which mostly targeted T.A.Z.’s in open fields and deserted urban spaces. Raving outside of the commercial sphere had always already been an act of dissent, of rebellion, but was now pushed towards the margins even further. The state-fueled suspicion towards the T.A.Z. in the UK created a different paradigm for reading the rave than in other countries. It made rave’s optimism less gratuitous, it put something real on the line. Real freedom of real bodies, not just the freedom otherwise known as consumerism.

20.

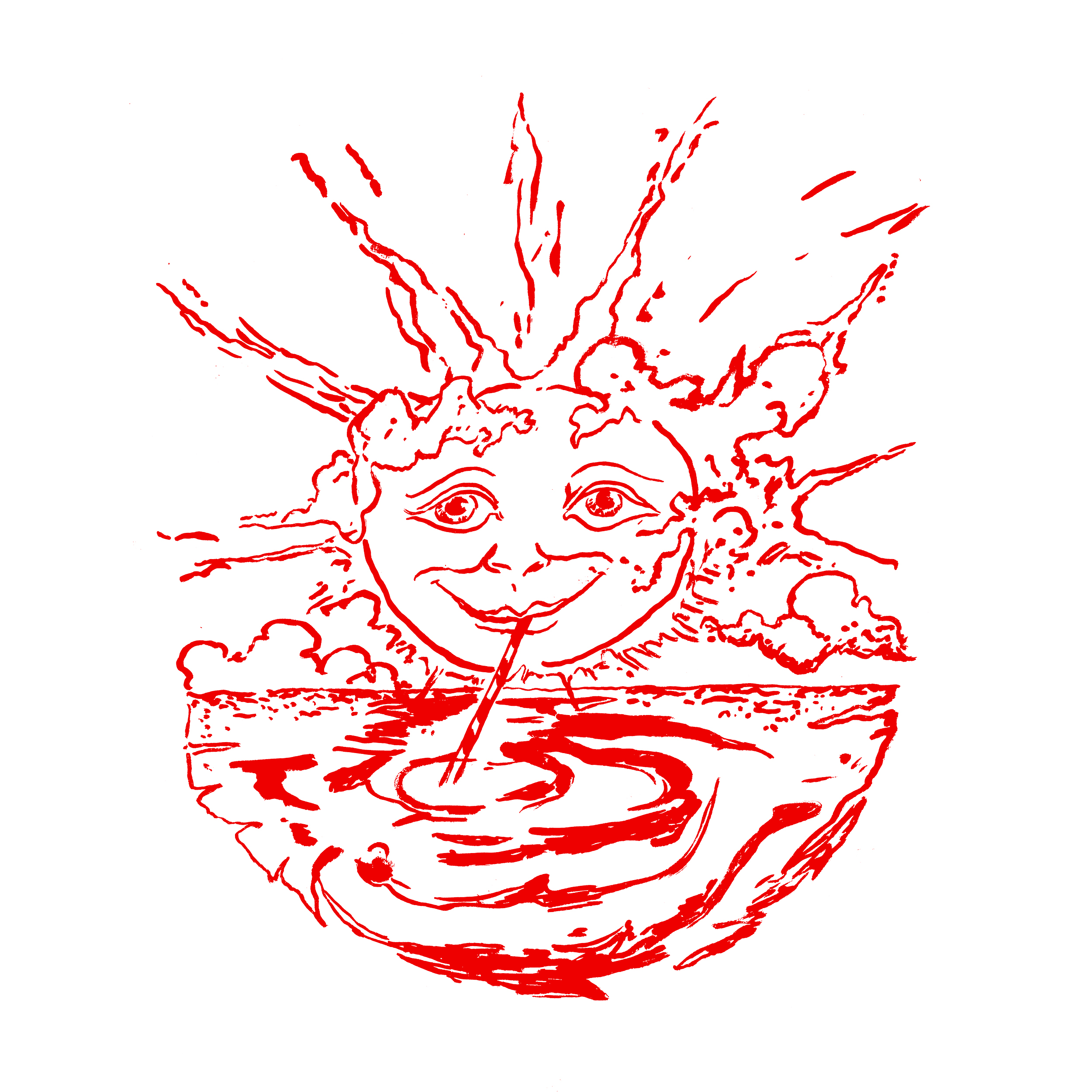

Illustration by and courtesy of Martin Groch (2021)

It is with this specific local history in mind that I read Mark Fisher’s short but crucial text on rave: “Baroque Sunbursts”, quoted at the beginning of this text. An avid raver in the 1980s and 1990s himself, witnessing the explosion of new musical genres and subgenres from house to acid to jungle, the new millennium proved disappointing to Fisher. What was once the promise of the arrival of the future, fueled by machinic desire, the early world wide web and the millennium bug’s creative destruction, turned out to be same old same old.

Although enthralled by the constant musical innovation of the era - with a new electronic genre each month, a period he describes as a “recombinatorial delirium, which made it feel as if newness was infinitely available”17 – Fisher seems to have never shared in eighties optimism in the first place. He understood the emergence of the collective euphoria of rave as a pharmakon against isolation and looming crisis.

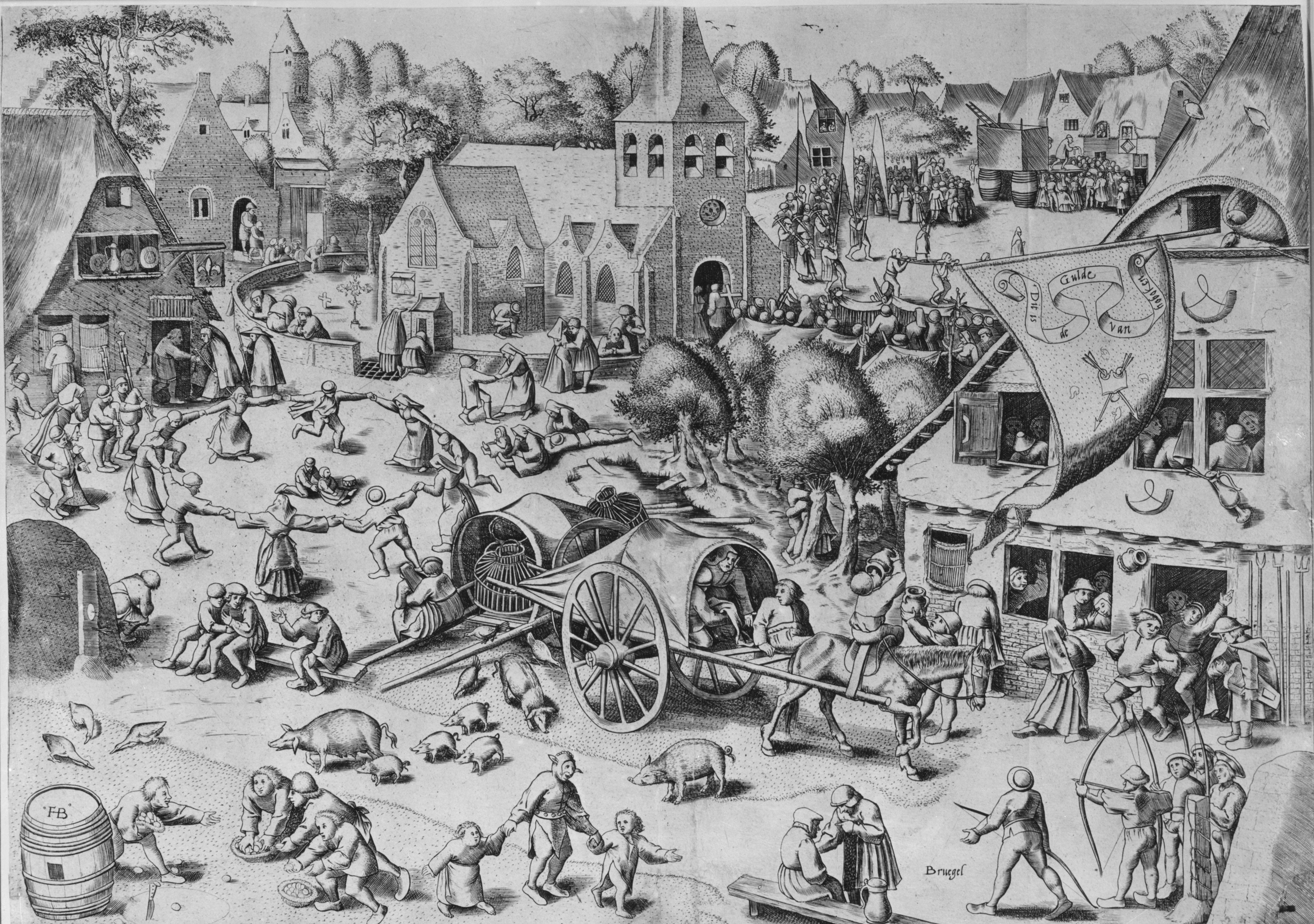

Fisher connects the “exorcism” of rave by the Criminal Justice Act of 1994 to the crushing down of folkloric culture by the bourgeoisie during the emergence of capitalism. Rave had to be criminalized because just as squatting, it contains “the spectre of a world that could be free”18 , Fisher states, quoting Herbert Marcuse.

Fisher reminds us of premodern scenes of rural collective delirium, such as the fair and the carnival, interstitial spaces “where the boundaries between bodies collapse, where faces and identities slip”19 , blending commercial activity with rural fun and the chaos of drunken masses. When the bourgeoisie started to accumulate and enclose the land in the process of primitive accumulation, these sites began to cause anxiety. It was not only the chaos and unpredictability of mass gatherings. “It was the illegitimate ‘contamination’ of ‘pure’ commerce by carnival excess and collective festivity which troubled bourgeois writers and ideologues. The problem which they faced, however, was that commercial activity was always-already tainted with festive elements. There was no ‘pure’ commerce, free from collective energy. Such a commercial sphere would have to be produced, and this involved the subduing and ideological incorporation of the ‘marketplace’ as much as it entailed the domestication of the fair.”20

This is what rave reminds us of, in Fisher’s strikingly optimistic (too euphoric?) but marvelous words:

Rave’s ecstatic festivals revived the use of time and land which the bourgeoisie had forbidden and sought to bury. Yet, for all that it recalled those older festive rhythms, rave was evidently not some archaic revival. It was a spectre of postcapitalism more than of pre-capitalism. Rave culture grew out of the synthesis of new drugs, technology and music culture. MDMA and Akai-based electronic psychedelia generated a consciousness which saw no reason to accept that boring work was inevitable. The same technology that facilitated the waste and futility of capitalist domination could be used to eliminate drudgery, to give people a standard of living much greater than that of pre-capitalist peasantry, while freeing up even more time for leisure than those peasants could enjoy. As such, rave culture was in tune with those unconscious drives, which as Marcuse put it, could not accept the ‘temporal dismemberment of pleasure... its distribution in small separate doses’. Why should rave ever end? Why should there be any miserable Monday mornings for anyone? 21

The Kermesse at Hoboken, Peter Brueghel The Elder (1559). Pen and brown ink, contours incised for transfer. Samuel Courtauld Trust: Lee Bequest, 1947.

21.

Even in the abstract setting of Echoic Choir, archaic culture resonates. A large part of the composition is structured as a hocket. As a single melody divided over different voices like pieces of a puzzle, the hocket is a choral technique already found in the music of the 11th century, as well as in various local music traditions all over the world today. It creates a dynamic, spatial dispersion of the melody. In Echoic Choir, the hocket is another echo of the expression and experience of the collective. For the melody to be heard, each voice is needed. One single voice can only stutter. Like a single body on the dance floor will be shivering in the a/c.

The term ‘hocket’, as I found out, is derived from the French word hoquet, which means ‘shock, sudden interruption, hitch, hiccup’. Is it farfetched, along the lines of homonymy, to think of the styles of dancing that emerged on the dance floor, such as gabber’s signature style hakkûh?

22.

We’ve lost the plot, they chanted (but it returned). The recent reappraisal of gabber culture and hardcore techno by the more highbrow strata of society (see, for example, the excellent archival digging of Gabber Eleganza, the music of conceptronica artists, or the institutional blessings of institutes like the Museion in Bolzano) finally understand how bafflingly radical this paradigm once was and in fact still is. As a friend said while introducing me to Dj Dano’s 1994 experimental track ‘120-9000BPM’: “Stockhausen would have loved this.”

23.

Rave has always cultivated an explicit relation to history. In a Dutch documentary on acid house parties from 1988, a journalist asks a raver: is this the sound of the eighties? No, the raver yells. This is the sound of the new millennium.

The future was ostensibly hailed. Finally it had arrived. But instead of the future, all that we found was the present. An intensified, nauseating present, an endless succession of apocalyptic NOWs.

(Which reminds me of something I read in an interview with R.U. Sirius, the founder of 90s cyberpunk magazine Mondo 2000. On an alarmingly hot summer day he emails the journalist: “I’ve been trying to warn people that the apocalypse is boring.”22 )

24.

Apocalypse is boring. There is something about today’s endless chain of crises that is so numbing. It has stopped feeling like an event. There is no before and after the crisis. Crisis has become permanent, repetitive. Fisher took a lyric from Drake as the epigraph for his essay collection Ghosts of my life: “Lately I've been feeling like Guy Pearce in Memento”23 .

In Memento, a film from the beginning of the millennium directed by Christopher Nolan, the protagonist suffers from brain damage resulting in short-term memory loss and the inability to form new memories. Every day Guy wakes up and tries to piece together what happened to him and who killed his wife, using an intricate system of Polaroid photos and body tattoos, whose logic he has to figure out anew every day. Like Guy Pearce, Drake feels like he lives the same day every day, ignorant of yesterday, ignorant of his trauma, and uncertain of the future. The life of a hamster on a treadmill. An inescapable present, an endless succession of NOWs.

If we’re caught in the same cycle anyways, I’d rather be spending it on a dancefloor.

25.

The spectacular last lines of “Baroque Sunbursts”:

“From time to time”, writes Fredric Jameson in Valences of the Dialectic, “like a diseased eyeball in which disturbing flashes of light are perceived or like those baroque sunbursts in which rays of from another world suddenly break into this one, we are reminded that Utopia exists and that other systems, other spaces are still possible.” This psychedelic imagery seems especially apposite for the “energy flash” of rave, which now seems like a memory bleeding through from a mind that is not ours. In fact, the memories come from ourselves as we once were: a group consciousness that waits in the virtual future not only in the actual past. So it is perhaps better to see the other possibilities that these baroque sunbursts illuminate not as some distant Utopia, but as a carnival that is achingly proximate, a spectre haunting even – especially – the most miserably de-socialised spaces.24

26.

Sometimes I wonder if Fisher wasn’t too attached to the project of history. I admire his ceaseless, depressive rejection of the staccato status quo throughout his writings, and I understand how hauntology works not so much as a reaffirmation of the project of progress, but rather as an indictment of a totalizing system that is crushing us, that has crushed us already. This is what makes his saturnine affects political, as opposed to impotent.

But do we really need his nostalgia? What if we imagine a sort of negative-negative dialectics. Call it heterotopia instead of utopia. What I mean is a broken, fractured utopia, a moment in time in which another world is already expressed; not ephemeral and spectral, but as real presence. (I keep thinking of Fred Moten’s words in The Undercommons: “I believe in the world and want to be in it. I want to be in it all the way to the end of it because I believe in another world in the world and I want to be in that.”25 )

Could we think of the rave (the rave continuum) as carving out a sensational fold in space and time, without retroactively creating an image of lost utopia and lost wholeness, but inhabiting the fundamental contradiction that is the real of being? The vortex as rehearsal, as practice, learning to live with that Lacanian myth of the “Missing One”, the lack, the constitutive gap that not only cuts through the subject but also through time, through history. Rave can be that experience of contradiction, but this time with our consent. It is a chosen experience of negativity, of non-sovereignty, its endless repetition acting out a life of being not-whole, incoherent, of the ego and the body constantly dissolving and slipping away and melting into others and merging and falling down and tripping and going bad and climaxing and destroying and being destroyed and re-emerging and almost dying and making out and complaining and flying high on the boom boom boom.

And then, at that moment, the best moment of the night has passed, and you were too ecstatic to realize it was the best moment, and you ask around, what was that track, who knows this track, you wanted to be part of it, to be lifted up, but every time you’re too late.

- Mark Fisher, “Baroque Sunbursts”, in Nav Haq (ed.), Rave and Its Influence on Art and Culture (Antwerp: M HKA, London: Black Dog Publishing, 2016), 43. ↩

- Even a supposed ‘indie’ film like Mia Hansen-Løve’s Eden (2014) wasn’t resistant to the gravity of the familiar coming-of-age drama plot. ↩

- Persis Bekkering, Last Utopia, tr. by Susan Ridder. (Maastricht: Jan van Eyck Academy, 2021), xx ↩

- See e.g. Nav Haq (ed.), Rave , 12 . ↩

- Rainald Goetz, Rave (1998) trans. Adrian Nathan West (London: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020), 245 - 247. ↩

- “The Hardcore Continuum #1: Hardcore Rave” (1992), The Wire, 02/2013, https://www.thewire.co.uk/in-writing/essays/the-wire-300_simon-reynolds-on-the-hardcore-continuum_1_hardcore-rave_1992_. ↩

- Guillaume Dustan, In My Room. The Works of Guillaume Dustan, Volume 1. Ed. Thomas Clerc. Tr. Daniel Maroun (South Pasadena: Semiotext(e), 2021), 122. ↩

- Hakim Bey, “T.A.Z.: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism” (1985), The Anarchist Library. Last modified 04/15/2022, https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/hakim-bey-t-a-z-the-temporary-autonomous-zone-ontological-anarchy-poetic-terrorism. ↩

- Hakim Bey, “T.A.Z.”, 1985. ↩

- Hakim Bey, “T.A.Z.”, 1985 ↩

- Persis Bekkering, "Shouts of Desire in the Night. On Echoic Choir", Wiener Festwochen 2021. ↩

- Simon Reynolds, “The Hardcore Continuum #1: Hardcore Rave” ↩

- Paul B. Preciado, Testo Junkie. Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics in the Pharmacopornographic Era. Tr. Bruce Benderson (New York: The Feminist Press, 2013). ↩

- Jannah Loontjens, Roaring Nineties (Amsterdam: Ambo Anthos, 2016), 147. ↩

- Felix Denk and Sven von Thülen, Der Klang der Familie. Berlin, Techno and the Fall of the Wall. (2012) Tr. Jenna Krumminga (Norderstedt: Books on Demand, 2014), 81. ↩

- Nav Haq, Rave, 13. ↩

- Mark Fisher, Ghosts Of My Life. Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Winchester: Zero Books, 2014), 5. ↩

- Mark Fisher in Nav Haq (ed.), Rave, 42. ↩

- Ibid., 44. ↩

- Ibid., 43. ↩

- Ibid., 42-3. ↩

- Claire L. Evans, “Inside ‘Mondo 2000’, the cyberpunk magazine that never was”, Document Journal, 01/07/2021, https://www.documentjournal.com/2021/01/inside-mondo-2000-the-cyberpunk-magazine-that-gave-us-a-glimpse-of-the-utopian-future-that-never-was/ ↩

- Mark Fisher, Ghosts Of My Life. Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Winchester: Zero Books, 2014), 0. ↩

- Mark Fisher in Nav Haq (ed.), Rave, 46. ↩

- Stefano Harney and Fred Moten, The Undercommons. Fugitive Planning & Black Study, Wivenhoe/New York/Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013), 118. ↩

Persis Bekkering is a metamorphic writer, engaging with a wide spectrum of artistic disciplines. She is interested in the emotional landscape of the contemporary, searching for new narrative forms that reflect a present permanently marked by crisis. Her recent publications include (fictocritical) essays, art criticism and fiction. Her debut novel Een heldenleven (The Life of a Hero), published in 2018, was shortlisted for the ANV Debut Prize. Her second novel Exces, shortlisted for the BNG Bank Prize for Literature, was published in 2021, part of which has been translated in English as Last Utopia by the Jan Van Eyck Academy in Maastricht. Recent and forthcoming publications include texts for M HKA Antwerp, Girls Like Us, Extra Extra and NRC Handelsblad. With choreographer Ula Sickle she worked as dramaturg on the concert performances The Sadness (2020) and Echoic Choir (2021). She also teaches at the Creative Writing department of ArtEZ University of the Arts in Arnhem.

This contribution is an edited version of a presentation delivered at ECAL on March 28, as part of the 2022 Master Fine Arts Symposium "How Soon Is Now? Histories and Figures of Youth."